Robeson's Scholarly Work

Paul Robeson entered Rutgers College as a student on an academic scholarship. More importantly, he knew that he bore the substantial responsibility of achieving the great potential he had demonstrated earlier in life, both in the classroom and as an athlete. Constantly on Paul's mind was the example of his father, who had escaped from slavery, graduated from Lincoln University, faced and overcome adversity many times, and who was Paul's mentor and idol.

As you review the sources for Activity Two, keep in mind the social context of the period 1900-1920, which became a defining intellectual experience for Robeson's artistry, social activism and scholarship. In Activity Two, you are asked to examine sources in a defined sequence, and then respond to the question posed here. The first 2 sources establish a foundation upon which the other sources can be better understood. Place your response to the Activity Two question in the Electronic NJ Learning Forum.

Question for Discussion

To what degree did Robeson's scholarly work at Rutgers represent a commitment to social change during his undergraduate years and afterwards?

To answer this question, read text excerpts 1and 2. Then examine the remaining sources in chronological order by the date of their creation before beginning your response to the question.

Excerpts

-

TEXT EXCERPT #1: Excerpt from Family Reunion Address of 1918, "Loyalty to Convictions."

"Unbending. Despite anything. From my youngest days I was imbued with that concept. This bedrock idea of integrity was taught by Reverend Robeson to his children not so much by preachment…but, rather, but the daily example of his life and work….So I marvel that there was no hint of servility in my father's make up. Just as in youth he refused to remain a slave, so in all the yeas of his manhood he disdained to be an Uncle Tom. From him we learned, and never doubted it, that the Negro was in every way the equal of the white man. Ad we fiercely resolved to prove it." (Robeson, Here I Stand, 1958; 8, 9, 11)

- TEXT EXCERPT #2: W. E. B. DuBois, Excerpt from "The Talented Tenth" Essay (1903)

The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst, in their own and other races. Now the training of men is a difficult and intricate task. Its technique is a matter for educational experts, but its object is for the vision of seers. If we make money the object of man-training, we shall develop moneymakers but not necessarily men; if we make technical skill the object of education, we may possess artisans but not, in nature, men. Men we shall have only as we make manhood the object of the work of the schools—intelligence, broad sympathy, knowledge of the world that was and is, and of the relation of men to it—this is the curriculum of that Higher Education which must underlie true life. On this foundation we may build bread-winning skill of hand and quickness of brain, with never a fear lest the child and man mistake the means of living for the object of life…

The Function of the College-Bred Negro

…He is, as he ought to be, the group leader, the man who sets the ideals of the community where he lives, directs its thoughts and heads its social movements. It need hardly be argued that the Negro people need social leadership more than most groups; that they have no traditions to fall back upon , no long-established customs, no strong family ties, no well-defined social classes. All these things must be slowly and painfully evolved…

A More Elevated Purpose for the Industrial School

…Men of America, the problem is plain before you. Here is a race transplanted through the criminal foolishness of your fathers. Whether you like it or not the millions are here, and here they will remain. If you don't lift them up, they will pull you down. Education and work are the levers to uplift a people. Work alone will not do it unless inspired by the right ideals and guided by intelligence. Education must not simply teach work—it must teach Life. The Talented Tenth of the Negro race must be made leaders of thought and missionaries of culture among their people. No other can do this work and Negro colleges must train men for it. The Negro race, like all other races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men.

-

TEXT EXCERPT #3: Excerpts from Paul Robeson, Senior Thesis, Submitted May 29, 1919: "The Fourteenth Amendment: The Sleeping Giant of the American Constitution." Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives.

Of all the forces that have acted in strengthening the bonds of our Union, in protecting our civil rights from invasion, in assuring the perpetuity of our institutions and making us truly a nation, the Fourteenth Amendment is the greatest. The civil war and the following days of Reconstruction demonstrated clearly to the people that the unrestrained power of the States to alter their constitutions as their interests or passions might impel, greatly endangered their fundamental rights. Under this amendment, therefore, we find the essential rights of life, liberty, and property placed under the ultimate protection of the national government. What a change we find here from the spirit of 1787 when the Federal Constitution was adopted. At the time the States were exceedingly jealous of their rights and desired to limit as far as possible the activities or rather sphere of activity of the Central Government. Thus, the proposal of the first ten amendments which were applicable to the Federal Government only and not to the States.

…Before the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Constitution contained no definition of citizenship, either of the United States or of a State. It referred to a citizenship of the United States as a qualification for membership in the two houses of Congress and for the presidential office, but it did not declare what should constitute such citizenship. Prior to this, no one could be a citizen of the United States unless a citizen of a State according to the state constitution and laws according to leaders of states-rights parties and suggested by the United States Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision which declared that a man of African descent could not be a citizen of a State or of the United States as the United States had not the power to make him so.

…Nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, and property without due process of law. This phrase embodies one of the broadest and most far-reaching guaranties of personal and property rights. As Justice Matthews says in Yick Wo v. Hopkins, the term is one of those "monuments showing the victorious progress of the race in securing to men the blessings of civilization under the reign of just and equal laws so that the government of the commonwealth may be a government of laws and not of men." The general scope of the provision is to secure to every person, whether citizen or alien, those fundamental and inalienable rights of life, liberty, and property, which are inherent in every man, and to protect all against the arbitrary exercise of governmental powers in violation and disregard of established principles of distributive justice. This protection is the object and essence of free government, and without it true liberty cannot exist.

…So long as the Constitution of the United States continues to be observed as the political creed, as the embodiment of the conscience of the nation, we are safe. State constitutions are being continually changed to meet the expediency, the prejudice, the passions of the hour. It is the law which touches every fibre of the whole fabric of life which surrounds and guards the rights of every individual; which keeps society in place; which in the words of Blackstone, "is universal in its use and extent, accommodated to each individual, yet comprehending the whole community". This Amendment is a vital part of American Constitutional Law and we hardly know its sphere, but is provisions must be duly observed and conscientiously interpreted so that through it, the "Sleeping Giant of our Constitution," the American people shall develop a higher sense of constitutional morality.

-

TEXT EXCERPT #4: Paul Robeson, Valedictorian Address Delivered at Rutgers Graduation, June 10, 1919: "The New Idealism." Rutgers Targum, Vol. 50, 1918-19, pp. 570-571.

To-day we feel that America has proved true to her trust. Realizing that there were worse things than war; that the liberties won through long years of travail were too sacred to be thrown away, though their continued possession entailed the last full measure of devotion, we paid again, in part, the price of liberty. In the fulfillment of our country's duty to civilization, in its consecrating of all resources to the attainment of the ideal America, in the triumph of right over the forces of autocracy, we see the development of a new spirit, a new motive power in American life.

We find an unparalleled opportunity for reconstructing our entire national life and moulding it in accordance with the purpose and the ideals of a new age. Customs and traditions which blocked the path of knowledge have been uprooted, and the nation in place of its moral aimlessness has braced itself to the pursuit of a great national end. We can expect a greater openness of mind, a greater willingness to try new lines of advancement, a greater desire to do the right things, and to serve social ends.

It will be the purpose of this new spirit to cherish and strengthen the heritage of freedom for which men have toiled, suffered and died a thousand years; to prove that the possibilities of the larger freedom for which the noblest spirits have sacrificed their lives were no idle dreams; to give fuller expression to the principles upon which our national life is built. we realize that freedom is the most precious of our treasures, and it will not be allowed to vanish so long as men survive who offered their lives to keep it.

More and more has the value of the individual been brought home to us. Superficially, it would seem that we have acted regardless of individual human lives. But hardly a soldier has fallen who has not left a niche which can never be filled. The humblest soldier torn from this community has left a gap therein, for he was an integral part of it. Through the labors, sacrifices, and devotion, the nation has realized that its strength but reflects the strength and virtue of its members, and the value of each citizen is very closely related to the conception of the nation as a living unit. But unity is impossible without freedom, and freedom presupposes a reverence for the individual and a recognition of the claims of human personality to full development. It is therefore the task of this new spirit to make national unity a reality, at whatever sacrifice, and to provide full opportunities for the development of everyone, both as a living personality and as a member of a community upon which social responsibilities devolve.

We of the younger generation especially must feel a sacred call to that which lies before us. I go out to do my little part in helping my untutored brother. We of this less favored race realize that our future lies chiefly in our own hands. On ourselves alone will depend the preservation of our liberties and the transmission of them in their integrity to those who will come after us. And we are struggling on attempting to show that knowledge can be obtained under difficulties; that poverty may give place to affluence; that obscurity is not an absolute bar to distinction, and that a way is open to welfare and happiness to all who will follow the way with resolution and wisdom; that neither the old-time slavery, nor continued prejudice need extinguish self-respect, crush manly ambition or paralyze effort; that no power outside of himself can prevent a man from sustaining an honorable character and a useful relation to his day and generation. We know that neither institutions nor friends can make a race stand unless it has strength in its own foundation; that races like individuals must stand or fall by their own merit; to to fully succeed they must practice their virtues of self-reliance, self-respect, industry, perseverance and economy.

But in order for us to successfully do all these things it is necessary that you of the favored race catch a new vision and exemplify in your actions this American spirit. That spirit which prompts you to compassion, a motive instinctive but cultivated and intensified by Christianity, embodying the desire to relieve the manifest distress of your fellows; that motive which realizes as the task of civilization the achievement of happiness and the institution of community spirit.

Further, the feeling or attitude peculiar to those who recognize a common lot must be strengthened; that fraternal spirit which does not necessarily mean intimacy, or personal friendship, but implies courtesy and fair-mindedness. Not only must it underlie the closer relations of family, but it must be extended to the broader and less personal relations of fellow-citizenship and fellow-humanity. A fraternity must be established in which success and achievement are recognized and those deserving receive the respect, honor and dignity due them.

We, too, of this younger race have a part in this new American Idealism. We too have felt the great thrill of what it means to sacrifice for other than the material. We revere our honored ones as belonging to the martyrs who died, not for personal gain, but for adherence to moral principles, principles which through the baptism of their blood reached a fruitage otherwise impossible, giving as they did a broader conception to our national life. Each one of us will endeavor to catch their noble spirit and together in the consciousness of their great sacrifice consecrate ourselves with whatever power we may possess to the furtherance of the great motives for which they gave their lives.

And may I not appeal to you who also revere their memory to join with us in continuing to fight for the great principles for which they contended, until in all sections of this fair land there will be equal opportunities for all, and character shall be the standard of excellence; until men by constructing work aim toward Solon's definition of the ideal government--where an injury to the meanest citizen is an insult to the whole constitution; and until black and white shall clasp friendly hands in the consciousness of the fact that we are brethren and that God is the father of us all.

-

TEXT EXCERPT #5: Statement by Rutgers University Conferring Master of Arts Honorary Degree on Paul Robeson, June 11, 1932. Courtesy of Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives.

Released Saturday, June 11, after 11:00 a.m. Honorary Degree conferred at 166th Commencement of Rutgers University, June 11, 1932.

PAUL LEROY ROBESON:

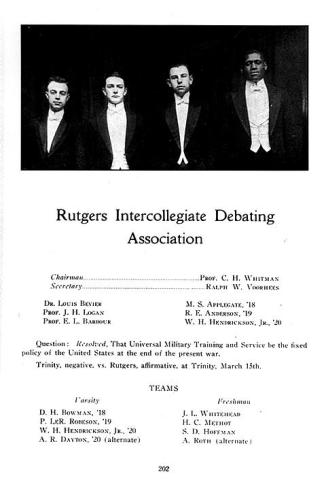

Graduate of Rutgers in the class of 1919 and held in high regard on the campus by your fellow-students; member of Phi Beta Kappa, and at the same time four-letter man, playing on twelve varsity athletic teams; chosen end on Walter Camp's All-American football team;

Seldom is it given to one man to bring joy into the hearts of his hearers by the arts of singing and acting as it has been given to you, and you have well discharged the trust which that gift implies. The lilt of your voice, the rich interpretations, have awakened sleeping souls, amused heavy forgetfulness to others, thrilled yet others with a new appreciation of the place of beauty in a commonplace world. you have contributed richly to the happiness and culture of countless thousands;

These are achievements which cannot be measured nor appraised but we, your associates in the life of Rutgers, can honor you for them and pay you our tribute. In token of that tribute, I confer upon you the degree of MASTER OF ARTS.

-

TEXT EXCERPT #6: Paul Robeson, "Some Reflections on Othello and the Nature of Our Time." The American Scholar, Autumn 1945.

Permission to reprint this article courtesy of The Phi Beta Kappa Society.It was deeply fascinating to watch how strikingly contemporary American audiences from coast to coast found Shakespeare's Othello--painfully immediate in its unfolding of evil, innocence, passion, dignity and nobility, and contemporary in its overtones of a clash of cultures, of the partial acceptance of and consequent effect upon one of a minority group. Against this background the jealousy of the protagonist becomes more credible, the blows to his pride more understandable, the final collapse of his personal, individual world more inevitable. But beyond the personal tragedy, the terrible agony of Othello, the irretrievability of his world, the complete destruction of all trusted and sacred values--all these suggest the shattering of a universe.

To an actor the question arose: how make personal and convincing such lines as "when I love thee not chaos is come again." "Methinks it should be now a huge eclipse of sun and moon, and that the affrighted globe should yawn at alteration," or, "It is the very error of the moon--she comes more nearer earth than she was wont and makes men mad." The desired approach was suggested by Professor Theodore Spencer in his most illuminating Shakespeare and The Nature of Man. For in actual fact Othello's world was breaking asunder as Medievalism was ending, and the new world of the Renaissance beginning.

So now, interestingly enough, we stand at the end of one period in human history and before the entrance of a new. All our tenets and tried beliefs are challenged.

We have been engaged in a global war, a war in which the capacity of our productive processes and techniques have clearly presaged the realization of new productive relationships in our society--new conceptions and assumptions of political power, with all sections of the people claiming a place in the social order. And what a vista lies before us! This can be the final war. It is possible to solve once and for all the problem of human poverty, to attain a speedy freedom and equality for all peoples.

In this shaping of our new world and amid its consequent clashes and sharp struggles, where should we stand? What should be our domestic direction? What should be our policy toward the England of Churchill or of British labor, toward France, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, China, Africa the Near East, Spain, Latin America (especially the Argentine), and most importantly, toward the Soviet Union?

A tremendous responsibility to understand these problems rests upon every American. Certainly our influence must be upon the side of progress, not reaction; upon the side of the freedom-loving peoples and the forces of true liberation everywhere--peoples and forces expressing their wills in various democratic forms, liberal, cooperative and socialist.

An added responsibility rests upon the liberal intellectual--the scientist, the member of the professions, the scholar, the artist. They have an unparalleled opportunity to lead and to serve. But to fulfill our deep obligations to society we must have faith in the whole people, in their potential and realized abilities. This faith, in our new world of today, must include the complete acceptance of the assumption of positions of great power by true representatives of the whole people, the emergence into full bloom of the last estate, the vision of no high and no low, no superior and no inferior--but equals, assigned to different tasks in the building of a new and richer human society.