Robeson's Athletic Experiences

Instructions

Examine the photographs and text excerpts provided here. Based upon this evidence and your study of U. S. history during the period 1865-1930, construct a response to this question.

Question for Discussion

How did Robeson's relationships with white students and faculty compare with the treatment of Afro-Americans by whites in the North during the period from 1880-1920?

Excerpts

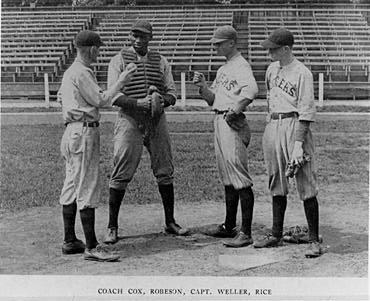

- TEXT EXCERPT #1: First Day of Football Scrimmage at Rutgers, 1915

One boy slugged me in the face and smashed my nose, just smashed it. That's been a trouble to me as a singer every day since. And then when I was down, flat on my back, another boy got me with his knee, just came over and fell on me. He managed to dislocate my right shoulder.

Well, that night I was a very, very sorry boy. Broken nose, shoulder thrown out, and plenty of cuts and bruises. I didn't know whether I could take any more. But my father—my father was born in slavery down in North Carolina—had impressed me that when I was out on a football field or in a classroom or just any where else I wasn't there just on my own. I was the representative of a lot of Negro boys who wanted to play football and wanted to go to college, and as their representative, I had to show that I could take whatever was handed out. (NY Times, quoted in Brown, 1997, 60-61)

- TEXT EXCERPT #2: Paul Robeson Recuperating from Injuries Noted In Excerpt #1, 1915

"Kid, if you want to quite school, go ahead, but I wouldn't like to think, and our father wouldn't like to think, that our family had a quitter in it." (William Robeson, Paul Robeson's oldest brother, quoted in Brown, 1997, 61)

- TEXT EXCERPT #3: Paul Robeson Returns to the Football Team, 1915

I made a tackle and was on the ground, my right palm down on the ground. A boy came over and stepped hard on my hand. He meant to break the bones. The bones held, but his cleats took every single one of my fingernails off my right hand. That's when I knew rage!

The next play came around my end, the whole first-string backfield came at me. I swept out my arms—like this—and the three men running interference went down, they just went down. The ball-carrier was a first-class back named Kelly. I wanted to kill him and I meant to kill him. It wasn't a thought, it was just a feeling, to kill. I got Kelly in my two hands and I got him over my head—like this. I was going to smash him so hard to the ground that I'd break him in two, and I could have done it.

But just then the coach yelled, the first thing that came to his mind, he yelled: "Robey, you're on the varsity!" That brought me around. We laughed about it often later. They all got to be my friends. (NY Times, quoted in Brown, 1997, 61)

- TEXT EXCERPT #4: Paul Robeson and the 1915 Rutgers Football Banquet

A highlight for Freshman Robey was his attendance in December at New Brunswick's annual civic banquet for the football team, and he saved the menu of the dinner at Klein's Hotel as a souvenir. However, somebody had evidently fumbled the ball by inviting him, and never again would he attend the town's banquet honoring his team. Because he was black, in the succeeding years there would be no room for him at the inn, not even when he became the team's most honored player. As Robey's teammate and class president Bill Feitner, a retired engineer, explained: "In those days—and don't forget, that was many years ago—colored people were not accepted in hotels and public restaurants, and so whenever there was a banquet for the team, Paul always arranged, gracefully, to have some other place to go." It was, said Feitner, "a fine thing for him to do." (Brown, 1997, 64)

- TEXT EXCERPT #5: Rutgers vs. Washington and Lee, 1916: Final Score, 13-13

...The game against Washington and Lee was scheduled in conjunction with the sesquicentennial celebration of the founding of Rutgers (1766-1916). The visiting Southerners threatened to spoil the festivities by calling off the match unless they were spared the indignity of competing against a player they deemed racially inferior. Rutgers complied with their demand. As Bill Feitner, one of Robey's teammates blandly recalled: "They refused to play if Robeson played, so since they were in New Brunswick and all other arrangements having been made, there was nothing Sandy [Coach Sanford] could do but concede. I played Robey's position in that game." (Brown, 1997, 68)

- TEXT EXCERPT #6: Letter from Rutgers Graduate James D. Carr, Class of 1892 and Reply from Rutgers to Carr. Courtesy of Rutgers Special Collections and University Archives.

James D. Carr, the second Afro-American student to attend Rutgers College, and a graduate of the class of 1892, authored this letter to Rutgers president William H. S. Demarest in response to the exclusion of Paul Robeson from the Rutgers-Washington and Lee football game in 1916. A reply to Carr's letter from Rutgers follows.

City of New York, Law Department, Bureau for the Recovery of Penalties, Municipal Building, Fifteenth Floor

June 6, 1919.

President William H. S. Demarest, LL.D.

Rutgers College,

New Brunswick N. J.

Dear Sir:-

During the celebration of the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Rutgers College a statement appeared in the public press that Washington and Lee University, scheduled for a football game with Rutgers, had protested the playing of Paul Robeson, a regular member of the Rutgers team, because of his color. In reading an account of the game, I saw that Robeson's name was not among the players. My suspicions were immediately aroused. After a considerable lapse of time, I learned that Washington and Lee's protest had been honored, and that Robeson, either by covert suggestion, or by official athletic authority, had been excluded from the game.

You may imagine my deep chagrin and bitterness at the thought that my Alma Mater, ever proud of her glorious traditions, her unsullied honor, her high ideals and her spiritual mission, prostituted her sacred principles, when they were brazenly challenged, and laid her convictions upon the altar of compromise.

Is it possible that the honor of Rutgers is virile only when untested and unchallenged? Shall men, whose progenitors tried to destroy this Union, be permitted to make a mockery of our democratic ideals by robbing a youth, whose progenitors helped to save the Union, of that equality of opportunity and privilege that should be the crowning glory of our institutions of learning?

I am deeply moved at the injustice done to a student of Rutgers, in good and regular standing, of good moral character and splendid mental equipment, - one of the best athletes ever developed at Rutgers, - who, because guilty of a skin not colored as their own, was excluded from the honorable field of athletic encounter, as one inferior, and from those lists in which so many competitors for glory were engaged, in which he had formerly been, and into which, with a humiliating tardiness, he was afterwards admitted. He was robbed of the honor and glory of contending in an athletic contest for his college before an assembled multitude composed of representative men and women, of various avocations, from all the corners of the earth. Not only he, individually, but his race as well, was deprived of the opportunity of showing its athletic ability, and perhaps, its athletic superiority. His achievements on that day may have been handed down as traditions not only to honor his Alma Mater, but, also, to honor himself, individually, and his race, collectively. What an awful spectacle, one of Rutgers' premier athletes on the sidelines because of his color! Can you imagine his thoughts and feelings when, in contemplative mood, he reflects in the years to come that his Alma Mater faltered and quailed when the test came, and that she preferred the holding of an athletic contest to the maintenance of her honor and her principles?

I am provoked to this protest by a similar action of the University of Pennsylvania, heralded in the public press less than two weeks ago. Annapolis protested the playing of the Captain of one of the athletic teams of the University of Pennsylvania, a Colored man. Almost unanimously his fellow athletes decided to withdraw from the field and cancel the contest. In this, however, they were overruled by the athletic manager, who ordered the games to proceed. One of the University's premier athletes on the side lines because of his color! Such prostitution of principle must cease, or the hypocrisy must be exposed.

The Trustees and faculty of Rutgers College should disavow the action of an athletic manager who dishonored her ancient traditions by denying to one of her students, solely on account of his color, equality of opportunity and privilege. If they consider an athletic contest more than the maintenance of a principle, then they should disavow the ideals, the spiritual mission and the lofty purposes which the sons of Rutgers have ever believed that they cherished as the crowning glory of her existence. May we ever fervently pray that the Sun of Righteousness may shine upon our beloved Alma Mater, now growing and blossoming into the full fruition of her hopes.

Very respectfully yours,

James D. Carr

Rutgers '92

REPLY TO CARR LETTER FROM RUTGERS

June 16, 1919

Mr. James D. Carr

258 West 53rd. Street,

New York City

My dear Mr. Carr: -

I have your letter with regard to Mr. Robeson and am sorry that there was any incident such as you relate. I have a vague recollection of some discussion at that time but have not clearly in mind the exact details. It is entirely possible to say, however, that Mr. Robeson has received in a very constant and prevailing way the highest regard from every one in all relations as he deserved. He has been an excellent student, making Phi Beta Kappa and was one of the three speakers in the Commencement program. Among the students in athletic relations and otherwise he has been much respected. If there was a single untoward incident in his four year's record, I am sorry.

With best regards,

Very sincerely yours,

(no signature evident)