Clearly, women played active and public roles in WWII, yet nearly two-thirds of the adult female population did not hold employment outside their homes or serve in the military. Instead, they worked on behalf of the war through their own communities. For example, women in Chinese communities formed chapters of the New Life Movement to organize women for war relief efforts. These and millions of other women gave their time and energy to the Red Cross and the Office of Civil Defense. They provided entertainment to military men and women at USO canteens. And they sold war bonds, raised victory gardens, canned their own foods, collected tin cans and newspapers for recycling, and stretched their families' food and gasoline rationing stamps as far as they would go. (Riley 283).

Printed on the inside of War Ration Book No. 2 were the words "This is your Government's guarantee of your fair share of goods made scarce by war." The statement is telling. To force an unconditional surrender from the axis powers, the US government needed to secure Americans' wholehearted support. Officials hoped to ensure public commitment by using the equal distribution of high-status and familiar foods through mandatory food rationing to increase American's physical and psychic satisfaction. To maintain public approval or at least tolerance of rationing, government propaganda campaigns used images of food to depict American society as stable, abundant, and unifed. These campaigns were aimed particularly at securing the support of American women, who were chiefly responsible for family food consumption (Bentley intro).

Moreover, war brides provided a generally unrecognized support system for the armed forces. Between 1940 and 1943, one million more marriages occurred than prewar rates would have predicted. Some 8%, or four to five million women married servicemen. As war brides, the women traveled all over the country to live on or near bases, where they joined the Red Cross, volunteered as motor pool drivers, worked in hospitals and United Service Organizations (USOs), and supplied myriad other services. In 1944, one journalist described war brides as "wandering members of a huge unorganized club" but neglected to comment on their invaluable contributions to the war effort. (Ibid.)

So, how did the United States Government recruit women when the country as a whole had conditioned all of them to believe they were regarded as a flexible labor supply to be pulled out of the home when needed and pushed back when not? In 1941 an enigmatic situation existed; women had been lectured for better than a decade on their responsibilities as wives and mothers, and had been advised to avoid paid employment unless it was an absolute necessity. Now the government had to recast the image of women as potential workers. (Riley 278).

Thus, the War Manpower Commission (WMC) and the Office of War Information (OWI) faced a huge challenge in mobilizing women workers. Created in April of 1942 to plan placement, training, program review, labor utilization, and selective services, the WMC launched three public-message campaigns to attract women into the workforce. Especially in areas of the country experiencing labor shortages, the WMC used propaganda films, posters, billboards, and radio personalities. (Ibid.)

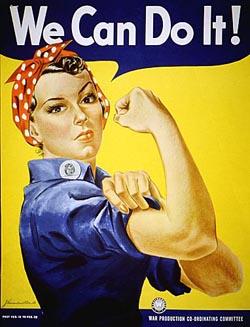

Rosie the Riveter

Initially, the War Advertising Council, an agency of the WMC, and the OWI emphasized the good wages women could earn. Next came the characer of "Rosie the Riveter." Much like the famous "Uncle Sam Wants You" poster, Rosie the Riveter posters soon plastered walls and sides of buildings everywhere. Rosie also appeared in newspapers, magazines, and advertisements. Dressed in overalls, her hair covered by a bandanna, Rosie called out to housewives across the land to join the army of the employed. (Riley 279).

Rosie quickly fired the public's imagination. Movies appeared with such titles as Swing Shift Maisie. Magazines ran articles proclaiming, "I Take Part in the War Effort," while advertisements declared, "There's a new woman today doing a man's job so that he may fight and finish this war sooner." Songs called "Rosie the Riveter" and "We're the Janes who Make the Planes" became instant hits. (Ibid.)

Because the OWI believed that effective propaganda included "highly emotional, patriotic appeals," the campaign also developed a "feminine" dimension. Advertisements compared acetylene torches to vacuum cleaners, arguing that women could handle any kind of machinery. The agency encouraged the design of special fashions to guarantee "vain" women the ability to look glamorous while working. It distributed war recruitment literature and posters that stressed a woman's patriotic duty to her country: "The More Women at Work- The Sooner We'll Win," but it also played on a woman's sense of loss and her duty to her man: "Longing Won't bring Him Back Sooner- Get a War Job!" (Ibid.)

The wartime propaganda directed at women had two major effects; it created an image of women as dynamic citizens, and it helped to persuade millions of them to go to work. Lured by high and the nation's new image of women, American women poured into the labor force. Between 1940 and 1945, female workers increased by slightly more than 50%. In 1940, 11,970,000 women worked outside of their homes; in 1945, 18,610,000 did so. In other words, the proportion of women working for wages, three-fourths of whom were married, rose from 17.6 to 37% in this period. (Ibid.)

Women with small children also took wartime jobs. To assist them, in 1942 the Lanham Act established Child Care Centers in forty-one states. The government intended these centers only as an emergency wartime measure rather than a sign of women's acceptance into the labor force or a permanent perquisite for women. After the war, the centers were closed or converted to other uses. (Ibid.)

During the war, women replaced male workers in ordnance plants, shipyards, aircraft factories, and steel mills. But they also seized newly opened opportunities as musicians, scientists, doctors, attorneys, university professors, governmental officials, athletes, and teachers. The federal government itself hired a huge number of women. In 1939, less than 200,000 women worked in civil service jobs; in 1940 they totaled more than one million- an increase of 540%. (Ibid.)

For their labor, women received high wartime wages, regulated hours, decent working conditions, and such support services as canteens and the day care provided through the Lanham Act. Moreover, the Women's Bureau, the War Production Board and the War Manpower Commission all endorsed the principle of equal pay. In 1942, the one agency that had the power to enforce equal pay- the National War Labor Board- ordered equal wages for women who performed "work of the same quality and quantity" as male laborers. Although women continued to suffer inequitable pay because of lack of enforcement, the NWL had established the ideal of equal pay. (Ibid.)

In addition, wartime gains for women included the end of age requirements for teachers and bans against hiring married women teachers. Also, approximately half of black domestic servants found jobs with higher pay and more status, while other women of color and disabled women also obtained employment in factories. (Ibid.)

Unions also began to open memberships to women workers. Although many male workers still resisted working with women, some union leaders began to accept the idea of women wageworkers. From its inception in 1935, the CIO had admitted all workers and the AFL had long included the ILGWU as an affiliate, but now the AFL began to open membership in craft-oriented affiliates to women as well. By the end of the war, between 3 and 3.5 million women (including women of color) belonged to unions, an increase of over 12% since 1940. Yet the struggle for access to unions was not over for women; they still faced prejudice of male members, restricted membership, and exclusion from positions of leadership. (Ibid.)

Questions and Activities

- How did the government change the "image" of women in order to attract them to the workforce?

- Describe the long range social and economic gains made by women from their work during the war.

- Analyze the posters and draw some conclusions as to what emotions the government was trying to evoke.