Selman Abraham Waksman was born in Priluka, Russia on 22 July 1888. Waksman graduated from the Fifth Gymnasium in Odessa, Russia, and came to the United States in 1910 after he was refused admittance to the university because he was Jewish. He entered Rutgers University in 1911, where he worked with another Russian emigre, Dr. Jacob G. Lipman, whose primary research was on soil microbiology. Waksman graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1915 and received a Masters of Science the following year, at which time he became a naturalized citizen. In 1916, Waksman married a young woman he had known in Russia, Deborah Mitnik, and entered the University of California at Berkeley to study biochemistry. He received his Doctorate in 1918, having supported his graduate study by working part-time at the Cutter Biological Laboratories in Berkeley, California.

Waksman returned to Rutgers University in 1918 and began working as a microbiologist in the department of Soil Chemistry and Bacteriology at the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. He also held an appointment as a lecturer at Rutgers University. Until 1920 Waksman also worked part-time as bacteriologist for the Takamine Laboratories in Clifton, New Jersey, in order to supplement his income. Waksman became an associate professor at Rutgers in 1924 and achieved the rank of full professor in 1930. The following year he also became associated with the Woods Hole (Massachusetts) Oceanographic Institution, where he organized the division of maritime bacteriology. Waksman, who became head of the newly organized Department of Microbiology at Rutgers in 1942, also continued to serve as microbiologist of the Agricultural Experiment station.

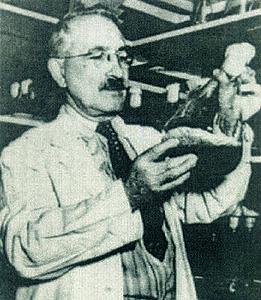

As a microbiologist, Waksman concerned himself primarily with soil organisms, particularly the actinomycetes on which he became the leading authority. Waksman's most important work was the isolation of a number of antibiotics from actinomycetes. The most important of these was streptomycin, isolated in 1942, which revolutionized the treatment of tuberculosis. Altogether, Waksman and his associates isolated 22 antibiotics (a term coined by Waksman), including actinomycin (1940), neomycin (1949), and candicin (1953). He also did notable work on such subjects as the production of enzymes and organic acids, on the decomposition of organic matter, including the building of humus and the utilization of peat, on edible fungi, on fermentation, and the role of microorganisms on metal corrosion. Waksman’s work resulted in the publication of some 500 authored and co-authored papers. He also wrote or edited 28 books.

His most significant practical contributions were as a consultant to Merck and Company in 1938, for whom he patented a number of organic acids and antibiotics. Rutgers benefited from Waksman's association with Merck through royalties as well as the establishment of a fellowship in the Department of Soils. Waksman later convinced Merck to relinquish its exclusive rights to streptomycin and allow the university to license it to other pharmaceutical companies. The large royalties for the drugs patent were used by the Rutgers Research and Educational Foundation, of which Waksman was the director, to establish and fund the Institute of Microbiology. After his retirement, it was renamed the Waksman Institute of Microbiology in his honor.

Selman Waksman, who became wealthy from his patent royalties, used the proceeds in a number of philanthropic ways. He established the Foundation for Microbiology to award research grants and scholarships in the field. Similar Waksman Foundations were established in Japan and France from the foreign rights to streptomycin and neomycin in order to support microbiology research in those countries. He also established a fund to enable immigrants or their children to study agriculture at Rutgers, and his wife established a scholarship fund for music students at Douglass College [part of Rutgers]. A scholar of Jewish history and a strong supporter of the state of Israel, Waksman was also involved in the establishment of the Institute of General and Industrial Microbiology at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa.

During his life, Waksman received numerous honors and awards for his scientific work. The most notable of these was, of course, his Nobel Prize [for Physiology/Medicine in 1952]. Among others, he was awarded the rank of Commander of the French Legion of Honor; the Leeuwenhoek Medal of the Netherlands Academy of Science, the Emile Christian Hansen Prize of the Carlsberg Laboratorium, Copenhagen, Denmark; the Mary Laker Award of the American Public Health Association; the Amory Award of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; and honorary degrees from many American and foreign universities.

In 1958 Waksman retired as director of the Institute of Microbiology, but remained at the university as professor emeritus with an office and research laboratory under his direction. Selman Waksman died on 16 August 1973 and was buried at Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

--Written by Paul Israel , who is the Managing Editor of the Thomas Edison Papers at Rutgers, and is excerpted from the biographical notes that accompany the Waksman Collection's catalog, Rutgers University Archives and Special Collections. Reproduction for educational purposes only--proper citation required.