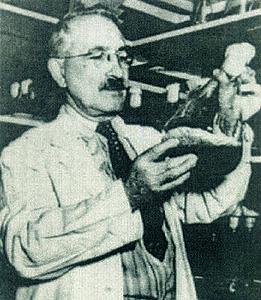

Dr. Selman Waksman (1888-1973)

Born in Prikula, Russia (near Kiev) in 1888, Selman Waksman entered Rutgers University as an undergraduate in 1911 and graduate with a Bachelor of Science degree in Agriculture in 1915. He completed his Master's Degree also at Rutgers while working as a research assistant in soil bacteriology at the New Jersey Experimental Agriculture Station. After working in California on his Ph. D in Microbiology he was invited back to Rutgers, where he worked his way up from Associate Professor to head of the Microbiology Department when it was organized in 1940. In 1949, after the discovery of neomycin , an Institute of Microbiology was established with Dr. Waksman as its first Director. Today this institute bears his name. In 1952, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology/Medicine for his work on antibiotics (including streptomycin) and their affect on tuberculosis. To view the Presentation Speech at the award ceremonies by Professor A. Wallgren, member of the Staff of Professors of the Royal Caroline Institute, click the link. While there you can view more biographical information on Dr. Selman Waksman. Although he officially retired from Rutgers in 1958, he still maintained an office and conducted research from time to time. He died in 1973.

Antibiotics and Dr. Waksman

The term itself, antibiotic, is a medical oxymoron of sorts. Literally, antibiotic means "anti-life" but yet we come to recognize the role they play in the treatment of common diseases. The work in antibiotics owes some credit to Dr. Louis Pasteur who discovered that some organisms destroyed others, but Waksman's work with soil bacteria led to a more aggressive look at Pasteur's methodology and breakthroughs in disease treatment. Antibiotics work to disrupt the normal functions of disease-causing cells, by disrupting normal cellular function or by destroying the disease causing cell's membrane. For more information on how antibiotics work, please click here.

Did you ever smell dirt? Go ahead, turn over the garden with a hand tool or a mechanical tiller, then dig your hands into the dirt and hold it to your nose. Smell that? The smell is coming from the bacteria in the soil. Recently, scientists working on asthma research have found reason to believe that children who come from squeaky clean environments where playing in the dirt is prohibited are more likely to contract asthma than kids who do play in the dirt.

Soil bacteria that developed a particular mold led to a breakthrough against the tubercle bacilli when the mold destroyed the tubercle bacilli--and streptomycin was born. It was used one year later at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN to treat a woman with tuberculosis and within a decade, TB, a very virulent and contagious disease, had been almost eradicated in the United States.

Waksman's work in soil bacteria was mostly in the category of actinomycetes. For a description click the previous link. For a more detailed look at the many types of actinomycetes, click here.

Waksman's Profitable Work

In the 1930's and 1940's, Dr. Waksman's work brought him into contact with representatives from major drug companies, some of whom had offices nearby to Rutgers University. A profitable relationship between pharmaceutical/chemical manufacturer Merck and Co. and the Institute emerged. Dr. Waksman could have used his discoveries to make himself rich, but chose to divert the larger share of the profits of his work to the Institute. His influence at Merck led Merck to give up its exclusive license on the manufacture of streptomycin so that it could be licensed to other companies in order to rapidly distribute this TB treatment.

This philanthropy did not keep Dr. Waksman from feeling the heat of controversy. One of his research assistants sued Waksman for a share of the profits from a discovery. The Schatz Case is covered in this unit using Waksman's own documents.

His notoriety, combined with his scholarly interest and love of Jewish history, led to the creation of the Institute of General and Industrial Microbiology at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa. Waksman was a strong supporter of the state of Israel. He was also very critical of the treatment, behind the Iron Curtain of Communism, of scientists by the Soviet Union. (These topics are under development as the archival information is made available). Waksman traveled extensively and the foreign profits from his work were used to establish microbiology research centers in Japan and France.

This unit will provide insight on the process of scientific discovery and the problems associated with it such as intellectual property rights and the role of politics and science. The documents that are presented here are used with the permission of the Rutgers University Archives by the Electronic New Jersey history project. Their reproduction for scholarly purposes is encouraged when proper credit is given. Check back with this site throughout the year as the high school teachers working on this project will be trying to add more information.

To visit the Waksman Institute at Rutgers University, click here.

To read an excerpt from the biography written by Paul Israel, whose notes accompanies the Waksman Collection at Rutgers, click here.