Where's The Garden?

New Jersey's image as a heavily industrialized and densely populated state stands in direct contrast to the state's slogan on its license plate that proclaims New Jersey to be "The Garden State." The slogan suggests that agriculture remains the dominant characteristic of the state's economy into the present day. To the casual turnpike traveler passing through New Jersey, the view from the automobile window presents a contradictory image of heavy industry, industrial pollution and widespread urbanization. The traditional agricultural image of barns and silos, grazing livestock and fields of crops appears to be in the minority. For a more complete explanation of the origin of the Garden State slogan, go to https://www.state.nj.us/nj/about/facts/nickname/.

Industrial growth has certainly characterized much of New Jersey's economy in the 20th century; however, the transformation from agriculture to industry has not been 100%. Agriculture, although diminished, remains a viable part of the New Jersey economy. While science and technology played a major role in the industrialization of New Jersey, it also gave rise to new ideas and theories that were tested in agricultural research laboratories and farm fields. This application of science and technology to problems confronting the farmer slowed the disappearance of New Jersey farms and produced a more bountiful harvest that to the present day brings food to your table. It also gave rise to new areas of agricultural enterprise in areas that previously had been deemed unsuitable due to sour or acidic soils. Thus, "The Garden State" slogan, while somewhat archaic as we enter the 21st century, still characterizes a shrunken but nonetheless important part of the state's economy.

The Lay of the Land

The State of New Jersey is actually a peninsula of land joined only on its northern border to neighboring New York State. New Jersey's eastern boundary is its coastline on the Atlantic Ocean while south and west the state is bordered by the Delaware River and the Delaware Bay. New Jersey is a small state in terms of area with its longest north-to-south distance measuring 166 miles from High Point in Sussex County to Cape May on its southern tip. New Jersey's width is even more narrowly defined in a range of 32-55 miles. Exclusive of its natural waters, New Jersey's area totals only 7500 square miles.

Two geographic provinces define New Jersey. These are the Atlantic Coastal Plain and the Appalachian Mountains. Dividing New Jersey at its narrow thirty-two mile waistband between Trenton and New Brunswick provides a natural separation between the two provinces. To the south and east lies the large coastal plain that at one time lay underneath the Atlantic Ocean. As waters receded, the plain was formed much like a great sandbar protruding above the surface of the adjacent waters. The soil patterns are largely comprised of loose sands, soft clay and marl allowing the coastal plain to function as a great aquifer retaining billions of gallons of water in subterranean reservoirs. While many areas of the Atlantic Coastal Plain in the 19th and 20th century supported traditional agriculture on family farms, significant acreage was under-utilized due to the high acidity levels of the soil or the unique flora and fauna of the New Jersey Pine Barrens.

The surface of the Appalachian Mountain region, characterized by ridges and valleys, proved itself unattractive and poorly suited for large-scale production agriculture. Today, as in the past, farmers in northwestern portion of the state engage mainly in small-scale livestock and/or dairy herd management, production of grains and grasses, and fruit husbandry.

Successes and Failures: Early Agriculture to 1850

The first recorded agriculture in New Jersey was that practiced by Native Americans. Their efforts mainly involved the gathering of wild plants, nuts and berries, and the growing of a handful of crops that sustained them through the long winter months.

The settlement of New Jersey by our colonial forefathers continued these practices but also involved an expansion of cultivated fields for production agriculture, the creation of small fruit orchards and the introduction of livestock. Not only did the individual farmer attempt to produce enough foods to provide for personal self-sufficiency but also to provide surpluses that could be used in barter or cash sales to others. In such cases, the modern elements of commerce (packaging/processing, reliable/economical transportation and market) were not readily at hand and crops were often converted to other products that had value and could be easily stored or transported. Examples include the making of maple syrup from sap, cider from apples and whiskey from corn. Products such as these removed the issue of a perishable inventory, could be stored in containers of local manufacture, reduced volume to more manageable size and created products that were of value for the cash or barter trade of the day.

Before 1850, production agriculture was largely a hit and miss proposition. Crops were planted and left almost to chance as to whether a bountiful harvest would result. Little thought was given to suitability of crops to specific soils, and use of specific fertilizers for specific purposes was largely unknown. Scientific agriculture was at best a vague notion and beyond immediate local concerns of rainfall, temperatures, natural disasters or fire, little effort was expended in exploring or understanding scientific principles with an eye to improving the odds of a successful harvest.

It's All in the Soil

Up to 1850, crop failures and worn out soil were all too common occurrences on New Jersey farms. To a largely uneducated farm community, the causes of these disasters were not understood and largely left to Providence. Without comprehending the reasons for such failures, the farmer was left to change occupations or move on to other farms and try again.

The late 1840's also marked the era of the Great Irish Potato Famine and the mass emigration of the Irish to America. Its impact on a significant population and the realization that unscientific agricultural procedures were largely responsible for the failure of the potato crop in successive years slowly gave rise in this country to the idea that science and technology could be employed to solve problems related to the successful growing and harvesting of specific crops. Initially, there was much conflict in the science community between many who pursued research strictly for the satisfaction of discovery and knowledge and others who saw the need for research and study directly linked to solving problems that limited farm income.

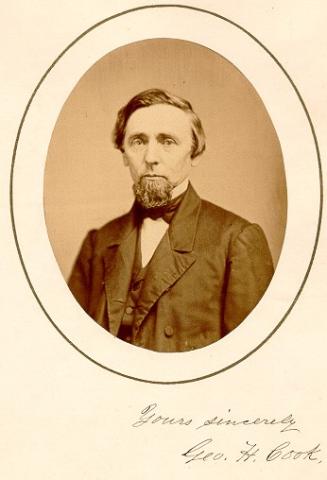

The same period marked a developing interest in geological surveys in the various older states experiencing agricultural production problems. Central to this was an interest in solving the relationship of trace elements in the soil to plant and human health. Surveys completed to date were a hodgepodge of scientific inquiry and careless observation written down in a variety of styles. New Jersey was to revolutionize soil properties research by funding their own extensive effort that led to publication in the early 1850's of the best of the surveys done to date. Largely the effort of George H. Cook, the publication of this survey brought Cook instant fame and provided the impetus for the state's involvement in agricultural research and direct support to farmers.

Cook had been an obscure professor of chemistry and natural sciences at Rutgers College. His duties were soon expanded when he received an appointment to be an assistant state geologist in charge of southern New Jersey. Taking to the field whenever his college teaching schedule would allow, Dr. Cook pioneered groundbreaking work in natural fertilizers and soil properties throughout South Jersey. He also used the above-mentioned survey as a means of becoming more familiar with the various farming conditions and problems to be found throughout the state.

The Morrill Land Act of 1862, passed by Congress for the entire nation and appropriating monies for agricultural research, provided Cook with the opportunity to press Rutgers to develop a school of agriculture and achieve Land Grant college status. This, in turn led to the establishment of a system of New Jersey Experimental Agricultural Stations that would carry on research on a number of fronts designed to be of direct benefit to the solving of the problems facing New Jersey's farmers. As these efforts came to fruition, the state also prescribed that there be instituted a series of free public lectures on agriculture. Dr. Cook had this job added to his many others, and no better person could have been picked. Believing the cause of agricultural advancement to be of prime importance, Cook travelled the length and breadth of New Jersey lecturing on agriculture to any who would listen. While travelling to these lectures, he would personally visit as many local farms as possible to personally identify successful practices, answer questions and gather a wealth of personal knowledge about New Jersey agricultural practices. Always with notebook in hand, he returned to New Brunswick and attempted to reply to each and every issue raised. It was said that no New Jersey farmer merely knew of Professor Cook; instead, they personally knew him, such was the extent of his travels and meetings throughout the state. Noted New Jersey historian John Cunningham summed it up with an even stronger statement that "no Rutgers personality ever has had an impact on New Jersey equal to that of George Hammell Cook." Such was the influence that George Hammell Cook had on New Jersey agriculture. It was altogether fitting that Rutgers honored him after death by naming their school of agriculture Cook College, a name that survives to the present day.

Agriculture in a New Century

By 1900, New Jersey was no longer a state where agriculture dominated. True, many farms were yet to be seen on the state's landscape, and the crop yield could be measured in millions of dollars. But, as elsewhere, New Jersey was transforming itself into an industrial state with large urban centers. This was especially true in the northeastern areas of the state. The advent of science and technology being applied to agriculture first under Cook and then others that followed, gave rise to developments in the southern half of the state that not only would defy describing New Jersey as only an industrial state but would promote two examples of agriculture enterprise, commercial cranberry and blueberry production, that would find prosperity in the 20th century. These enterprises may be used as examples of how science and technology melded together to change the agricultural landscape of the state.

Student Activities

- You have recently acquired a new penpal living in another part of the country. In an effort to get to know you better, the penpal asks you a number of questions. One expresses curiosity about your home state of New Jersey. Answer the question by writing a letter in which you provide your own personal view as to what is an accurate description of New Jersey that would help a non-resident more fully understand your home state.

- Do you enjoy living in New Jersey or would you prefer living elsewhere? Write a brief essay being specific as to what you like or dislike about New Jersey.

- The New Jersey Assembly is debating the merits of proposed legislation requiring that the slogan "The Garden State" be retained on vehicle license plates. The Governor opposes the legislation and is pushing for a more appropriate slogan for the 21st century. A vote is scheduled in seven days.

As a citizen of the state, write a letter to your assemblyman expressing your views on the subject. Be specific as to what action you want taken and why you take the position you do. Before starting, use resources in your school media center to determine an exact mailing address and the proper form for composing a letter to an assemblyman. - In an effort to compromise the views of the Governor and the Assembly over use of "The Garden State" slogan, the New Jersey Division of Motor Vehicles sponsors a statewide contest to seek new license plate designs. Use a 6x9 index card and design a new license plate to submit for the contest.

On the reverse side, accompany your new license plate design with 2-3 paragraphs of explanatory text supporting the rationale for your design.