Introduction

While children had for centuries been an integral part of the production process in urban and rural societies, with the development of mass production the employment of children in industrial workplaces became widespread. Abuses of children in mills, factories, mines and other industrial settings are documented in Europe and North American from the early nineteenth century, and the population shifts from rural to urban locations which accompanied industrialization provided employers with a large and vulnerable child labor force. Protecting children from workplace abuses was one of the earliest and best publicized reform movements of the Progressive Era. The National Child Labor Committee was formed in 1904, and soon thereafter hired photographer Lewis Hine to document the working conditions and abuses of children in U. S. industries, ranging from textile mills to coal mines and a host of other workplaces.

In 1906, Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana introduced the first federal legislation to regulate child labor, and in 1912 the first federal agency expressly devoted to the welfare of children was created, the U. S. Children's Bureau. Under the direction of Julia Lathrop and later Grace Abbott, the U. S. Children's Bureau investigated child labor issues, produced detailed reports on many aspects of child labor, and was an untiring advocate for federal legislation to limit workplace abuses against children. The first major federal legislation to regulate child labor was the Keating-Owens Act, passed by both houses of Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson in 1916. While many states, including New Jersey, had passed legislation regulating the hours and conditions of work for children between 1900 and 1916, this was the first time that the federal government had actively intervened with sweeping legislation to regulate child labor. The victory of reformers was short-lived however, as the U. S. Supreme Court in Hammer v. Dagenhart ruled the Keating-Owens act unconstitutional in 1917.

Despite the setback dealt to national legislation by the U. S. Supreme Court, the reporting and investigative work of the U. S. Children's Bureau, state agencies and non-governmental organizations such as the National Child Labor Committee and the Child Welfare League of America continued. Internationally, the development of minimum standards for the employment of children in the workplace was stimulated by the International Labour Organization's adoption in 1919 of two international agreements: the Convention Fixing the Minimum Age for Admitting Children into Industrial Employment and the Convention Concerning the Night Work of Young Persons Employed in Industry. While national governments who acceded to these international agreements agreed to meet the minimum standards included in the conventions, compliance was voluntary and no uniform monitoring system was implemented.

During the 1920s, efforts in the United States and abroad to regulate child labor were directly linked to increasing the attendance of children in formal schooling. Child labor reformers asserted that children who worked excessive numbers of hours often were truant from school, had poor academic performance and were poorly prepared for survival in a changing economy. Labor unions advocated the limitation of children in the labor force to prevent employers from using child labor as a substitute for adult union employees, noting that children were typically paid less than adults and were less likely to protest workplace abuses, such as hazardous working conditions and inadequate job training. In 1924, both houses of Congress passed a constitutional amendment regulating child labor, which was signed by President Coolidge and submitted to the states for ratification. The text of the proposed amendment is shown here.

Section 1. The Congress shall have power to limit, regulate and prohibit the labor of persons under 18 years of age.

Section 2. The power of the several states is unimpaired by this article except that the operation of State laws shall be suspended to the extent necessary to give effect to legislation enacted by the Congress.

Despite tireless efforts nationwide, the child labor amendment to the U.S. Constitution was not ratified, and by the advent of the New Deal in 1932, the United States still had no national standards for the protection of children in the workplace.

Your Task

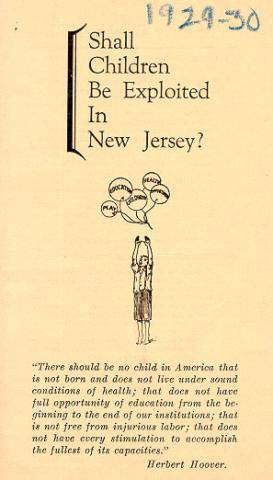

Explore the three sections of this curriculum module to answer the question shown here. As you explore the module sections, you will be asked to respond to questions and other activities related to primary and secondary sources located in the module. Use the links below the central question to explore the module sections.

Central question

Should the labor of children in the workplace be regulated by government?